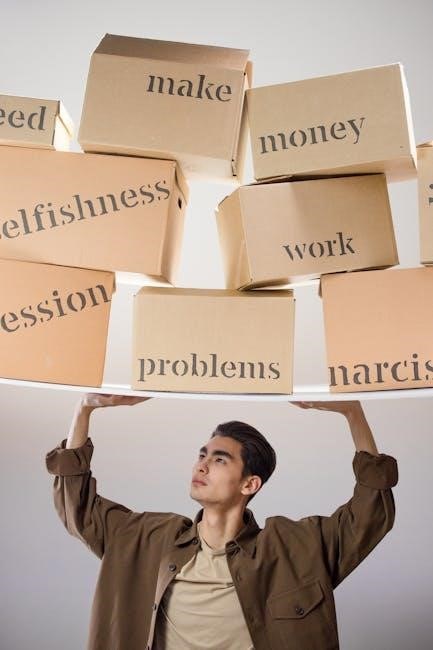

The Psychology of Money: A Comprehensive Overview

Exploring the behavioral patterns surrounding wealth, greed, and happiness, this overview delves into how individuals perceive and interact with financial resources, often deviating from purely rational calculations․

The core of financial psychology lies in recognizing that money isn’t solely about mathematical equations; it’s deeply intertwined with emotions, biases, and personal histories․ Traditional finance often assumes rational actors, yet human behavior consistently demonstrates otherwise․ Understanding these psychological nuances—like loss aversion and confirmation bias—is crucial for making sound financial decisions․

This field explores how our upbringing, experiences, and inherent cognitive limitations shape our attitudes towards saving, spending, and investing․ It challenges the notion that success is simply a function of intelligence or hard work, acknowledging the significant role of luck and risk․ Ultimately, grasping these concepts empowers individuals to build a healthier, more fulfilling relationship with money, moving beyond mere accumulation towards genuine financial well-being;

Morgan Housel and the Book’s Philosophy

Morgan Housel, author of “The Psychology of Money,” champions a perspective that financial success is less about what you know and more about how you behave․ He argues against optimizing for purely numerical gains, emphasizing the importance of long-term thinking and recognizing the influence of luck and risk․ Housel’s philosophy centers on understanding your own biases and building a financial plan aligned with your personal values․

He advocates for a “reverse obituary” exercise – imagining your future self and defining success beyond material possessions․ This approach encourages prioritizing contentment and freedom over relentless wealth accumulation․ Housel’s work challenges conventional financial wisdom, urging readers to focus on sustainable habits and emotional intelligence when navigating the complexities of money․

Why Traditional Financial Advice Often Fails

Traditional financial advice frequently falters because it assumes rational actors, overlooking the powerful influence of human emotion and cognitive biases․ It often prioritizes maximizing returns through complex strategies, neglecting individual risk tolerance and psychological needs․ This approach can lead to poor decisions driven by fear, greed, or the desire to keep up with others – the “herd mentality․”

Furthermore, standardized advice fails to account for personal values and unique life circumstances․ Housel highlights that financial success isn’t solely about knowledge; it’s about behavior․ Therefore, advice lacking psychological awareness often proves ineffective, even detrimental, as it clashes with inherent human tendencies․

Understanding Your Personal Relationship with Money

Recognizing that money’s influence extends beyond spreadsheets, this section explores how individual histories, beliefs, and emotional responses shape financial behaviors and overall well-being․

The Role of Luck and Risk

Acknowledging luck and risk is crucial, as attributing success solely to skill overlooks external factors․ Many financially successful individuals downplay the role of chance, fostering unrealistic expectations in others․ Similarly, failures are often attributed to poor decisions, neglecting the impact of unforeseen circumstances․

Understanding this duality is vital for developing a balanced perspective․ Recognizing luck doesn’t diminish achievement, but it promotes humility and empathy․ Conversely, accepting risk acknowledges that setbacks aren’t always indicative of personal failings․ This nuanced view encourages a more realistic assessment of financial outcomes, fostering resilience and informed decision-making, moving beyond simplistic narratives of meritocracy․

Defining “Enough” – The Importance of Contentment

The pursuit of wealth often lacks a defined endpoint, leading to perpetual dissatisfaction․ Establishing a personal definition of “enough” is paramount for achieving contentment․ This isn’t about limiting ambition, but rather recognizing the diminishing returns of excessive accumulation․

Many equate happiness with material possessions, constantly chasing an ever-shifting target․ However, true fulfillment often stems from non-financial sources – relationships, experiences, and personal growth․ Defining “enough” allows individuals to prioritize these values, reducing the pressure to constantly acquire more and fostering a sense of gratitude for what they already possess, ultimately leading to a more balanced life․

The Impact of Childhood Experiences on Financial Beliefs

Our earliest experiences with money, often shaped by our parents or guardians, profoundly influence our adult financial behaviors and beliefs․ Witnessing financial security or insecurity during childhood can create deeply ingrained attitudes towards saving, spending, and risk․

Individuals who grew up in households with financial scarcity might develop a heightened sense of frugality or anxiety around money, while those raised in affluence may exhibit different patterns․ These formative experiences aren’t necessarily rational, but they powerfully shape our subconscious financial programming, impacting decisions long into adulthood and influencing our overall relationship with wealth․

How Personal History Shapes Financial Decisions

Beyond childhood, our entire personal history – encompassing successes, failures, traumas, and cultural influences – molds our financial decision-making processes․ Past experiences create mental shortcuts and biases that affect how we perceive risk, evaluate opportunities, and react to market fluctuations․

For example, someone who experienced a significant financial loss might become overly cautious, avoiding investments altogether․ Conversely, a string of successful ventures could breed overconfidence and reckless behavior․ Understanding these deeply rooted patterns is crucial for recognizing and mitigating the influence of personal history on our financial choices, fostering more rational and informed strategies․

The Psychology of Saving and Spending

Examining the emotional drivers behind our financial habits, this section explores compounding’s power, the wealth-happiness paradox, and strategies for mindful spending and financial security․

The Power of Compounding – Beyond the Numbers

Compounding isn’t merely a mathematical formula; it’s a psychological challenge demanding patience and long-term vision․ Most underestimate its exponential growth potential, focusing on short-term gains instead․ Consistent, small investments over extended periods yield remarkable results, yet require resisting immediate gratification․

The true power lies not in achieving high returns annually, but in sustaining reasonable returns consistently․ Avoiding interruptions to the compounding process – like selling during market downturns – is crucial․ Understanding this requires shifting focus from specific numbers to the underlying principle of allowing time to work in your favor․ It’s about building wealth gradually, embracing the long game, and recognizing that consistent effort trumps sporadic bursts of brilliance․

The Paradox of Wealth: Status vs․ Happiness

The pursuit of wealth is often intertwined with a desire for status, yet material possessions rarely equate to lasting happiness․ Many chase visible displays of success – cars, homes, luxury items – believing they’ll bring fulfillment․ However, this external validation is fleeting and often leads to a hedonic treadmill, constantly needing more to maintain the same level of satisfaction․

True contentment stems from internal factors: strong relationships, personal growth, and a sense of purpose․ Wealth can enable happiness by providing freedom and security, but it doesn’t guarantee it․ Recognizing the distinction between wealth as a tool versus wealth as a status symbol is vital for cultivating genuine well-being and avoiding the pitfalls of comparison․

Controlling Your Spending: Avoiding Lifestyle Inflation

Lifestyle inflation – the tendency to increase spending as income rises – is a common financial pitfall․ While earning more seems positive, automatically upgrading your lifestyle can erode financial progress․ It creates a moving target, where increased income simply funds higher expenses, leaving little room for saving or investing․

Consciously controlling spending requires deliberate effort․ Instead of immediately indulging in upgrades, prioritize saving and investing a portion of any income increase․ Focus on experiences over possessions, and cultivate gratitude for what you already have; Building awareness of your spending habits and establishing clear financial goals are crucial steps in resisting lifestyle inflation and building lasting wealth․

The Importance of a Margin of Safety

A margin of safety, a core principle championed by investors like Warren Buffett, is crucial for navigating financial uncertainty․ It involves building a buffer into your financial plans to account for unforeseen events and inevitable errors in judgment․ This isn’t about pessimism, but rather acknowledging the inherent unpredictability of life and markets․

Practically, this means maintaining an emergency fund, avoiding excessive debt, and diversifying investments․ It’s about recognizing that forecasts are rarely perfect and that unexpected downturns will occur․ A margin of safety provides peace of mind and resilience, allowing you to weather storms without derailing your long-term financial goals․

Investing Psychology: Navigating Market Emotions

Understanding emotional biases—like loss aversion and overconfidence—is vital for sound investment decisions, preventing impulsive reactions driven by fear or greed in volatile markets․

Loss Aversion and its Impact on Investment Choices

Loss aversion, a core tenet of behavioral finance, demonstrates people feel the pain of a loss approximately twice as intensely as the pleasure of an equivalent gain․ This deeply ingrained psychological bias significantly influences investment decisions, often leading to irrational behavior․ Investors, fearing losses, may hold onto losing investments for too long, hoping they will recover, rather than cutting their losses and reallocating capital․

Conversely, they might sell winning investments prematurely to lock in gains, preventing potential further growth․ This fear-driven approach can hinder long-term portfolio performance․ Recognizing loss aversion is crucial for developing a disciplined investment strategy focused on long-term goals, rather than short-term market fluctuations, and mitigating its detrimental effects․

The Dangers of Overconfidence in Investing

Overconfidence, a pervasive cognitive bias, poses a significant threat to sound investment judgment․ Investors often overestimate their knowledge, abilities, and predictive power, leading to excessive trading and poor portfolio diversification․ This inflated self-belief can result in taking on unnecessary risks, chasing speculative investments, and ignoring crucial information that contradicts their preconceived notions․

The illusion of control further exacerbates this issue, as individuals believe they can skillfully time the market or pick winning stocks consistently․ Acknowledging the limits of one’s knowledge and embracing humility are vital for mitigating the dangers of overconfidence and fostering a more rational, long-term investment approach․

Long-Term Thinking vs․ Short-Term Gains

The tension between prioritizing immediate gratification and cultivating a long-term perspective is central to successful investing․ Market fluctuations and short-term noise often tempt investors to chase quick profits, abandoning their carefully constructed strategies․ However, consistently focusing on long-term goals, like retirement or financial independence, is crucial for weathering market volatility and maximizing returns․

Compounding, a powerful force in wealth creation, requires patience and discipline․ Resisting the urge to react impulsively to market swings and maintaining a consistent investment approach, even during downturns, allows investors to harness the benefits of time and compounding over the long haul․

Understanding Market Cycles and Investor Behavior

Markets inherently move in cycles – periods of expansion followed by contraction․ Recognizing these patterns isn’t about predicting the future, but understanding that downturns are inevitable and historically present opportunities․ Investor behavior often exacerbates these cycles; fear and greed drive irrational exuberance during booms and panic selling during busts․

Acknowledging that emotions significantly influence investment decisions is vital․ Understanding how herd mentality, loss aversion, and overconfidence impact market movements allows investors to make more informed choices, resisting the temptation to follow the crowd and instead focusing on their long-term financial goals․

Specific Behavioral Biases in Finance

Cognitive shortcuts, like confirmation bias, anchoring, and herd mentality, systematically distort financial judgment, leading to suboptimal decisions and potentially significant investment errors․

Confirmation Bias and its Effects

Confirmation bias, a pervasive cognitive error, compels individuals to favor information confirming pre-existing beliefs while dismissing contradictory evidence․ In finance, this manifests as selectively seeking news supporting investment choices, ignoring warning signs, and overemphasizing positive narratives․ Investors exhibiting this bias might cling to losing stocks, rationalizing their decisions instead of acknowledging mistakes․

This skewed perception hinders objective analysis, fostering overconfidence and potentially disastrous portfolio outcomes․ The tendency to filter information reinforces existing viewpoints, creating an echo chamber that prevents learning from failures and adapting to changing market conditions․ Recognizing and actively challenging one’s own biases is crucial for sound financial decision-making․

Anchoring Bias in Investment Decisions

Anchoring bias occurs when individuals rely too heavily on an initial piece of information – the “anchor” – when making subsequent judgments․ In investing, this often involves fixating on a stock’s past price, even if current fundamentals don’t justify it․ Investors might perceive a dip from that initial price as a bargain, ignoring broader market trends or company-specific issues․

This cognitive shortcut can lead to irrational buying or selling decisions, hindering portfolio performance․ The initial anchor unduly influences perception, preventing objective assessment of true value․ Overcoming anchoring requires conscious effort to disregard irrelevant past data and focus on present-day realities and future prospects․

The Herd Mentality and its Consequences

The herd mentality, a powerful psychological force, drives investors to mimic the actions of a larger group, often disregarding their own independent analysis․ Fueled by emotional contagion and a desire to avoid being left behind, this behavior can create market bubbles and crashes․ Individuals assume collective wisdom, believing that if many others are buying (or selling), it must be the correct course of action․

However, following the crowd frequently leads to suboptimal outcomes․ It amplifies market volatility and encourages irrational exuberance or panic․ Resisting the herd requires discipline, a well-defined investment strategy, and the courage to go against prevailing sentiment․

Practical Applications of Psychological Principles

Applying insights from behavioral finance allows for crafting financial plans aligned with personal values, managing debt effectively, and fostering long-term investment success․

Building a Financial Plan Based on Your Values

A truly effective financial plan isn’t solely about maximizing returns; it’s deeply rooted in understanding what genuinely matters to you․ The “Psychology of Money” emphasizes aligning financial decisions with personal values, recognizing that wealth is a tool for achieving a fulfilling life, not an end in itself․

This involves identifying core beliefs and priorities – freedom, family, security, or experiences – and structuring your finances to support those aspirations․ Consider a ‘reverse obituary’ exercise, envisioning how you want to be remembered, and then building a plan that facilitates that legacy․ Prioritize spending on things that bring lasting joy and meaning, rather than chasing status symbols․ This value-driven approach fosters contentment and reduces the likelihood of impulsive, regretful financial choices․

Developing a Long-Term Investment Strategy

“The Psychology of Money” advocates for a long-term investment horizon, acknowledging that consistent, patient growth often outperforms attempts at market timing․ Resist the allure of short-term gains and focus on building a diversified portfolio aligned with your risk tolerance and financial goals․

Understand that market fluctuations are inevitable; avoid panic selling during downturns, recognizing that these periods can present opportunities․ Embrace compounding, allowing your investments to grow exponentially over time․ Prioritize minimizing costs and avoiding unnecessary complexity․ A simple, well-defined strategy, consistently executed, is far more likely to yield success than a convoluted, emotionally-driven approach․

Managing Debt and Avoiding Financial Stress

“The Psychology of Money” emphasizes the corrosive impact of debt on financial well-being and mental health․ Prioritize debt reduction, particularly high-interest obligations, to free up cash flow and reduce anxiety․ Cultivate a mindset of financial prudence, distinguishing between needs and wants, and avoiding lifestyle inflation․

Building a financial buffer – a “margin of safety” – is crucial for weathering unexpected expenses and reducing stress․ Regularly review your budget, track your spending, and automate savings․ Remember that financial freedom isn’t solely about accumulating wealth; it’s about having control over your finances and minimizing the emotional burden associated with money․

The Importance of Financial Education

“The Psychology of Money” underscores that formal financial education is often less impactful than developing a healthy relationship with money․ Understanding your own biases – confirmation bias, anchoring, herd mentality – is paramount․ Seek knowledge from diverse sources, but prioritize practical application and self-awareness․

Financial literacy isn’t about mastering complex investment strategies; it’s about cultivating sound judgment, long-term thinking, and emotional control․ Continuously learn, adapt your strategies, and recognize that financial success is a lifelong journey, not a destination․ Empower yourself with knowledge to navigate the complexities of the financial world effectively․

The Psychology of Wealth and Happiness

True wealth transcends possessions, fostering freedom and contentment; redefining success beyond material gain unlocks fulfillment, emphasizing experiences and giving back to others generously․

Redefining Success Beyond Material Possessions

The conventional pursuit of wealth often equates success with tangible markers – luxury cars, expansive homes, and visible status symbols․ However, a deeper understanding, as explored in behavioral finance, reveals a crucial disconnect between material accumulation and genuine happiness․ Morgan Housel’s work emphasizes a “reverse obituary” exercise, prompting reflection on how one wishes to be remembered, shifting focus from what was acquired to how life was lived․

This perspective challenges the notion that financial success is solely measured by net worth․ Instead, it highlights the importance of experiences, relationships, and personal growth․ True fulfillment arises not from possessing more, but from appreciating what one has and contributing positively to the world․ Redefining success in these terms fosters a more sustainable and meaningful path to lasting contentment, decoupling happiness from the relentless pursuit of material possessions․

The Relationship Between Money and Freedom

The core appeal of money, beyond its practical uses, lies in the freedom it affords․ This isn’t necessarily about extravagant lifestyles, but rather the capacity to control one’s time and choices․ As highlighted in explorations of financial psychology, the highest form of wealth isn’t a specific dollar amount, but the ability to do what you want, when you want, with whom you want․

This freedom manifests as reduced stress, increased autonomy, and the opportunity to pursue passions․ It allows individuals to detach from the necessity of constant work and embrace experiences that contribute to personal fulfillment․ Understanding this connection shifts the focus from accumulating wealth as an end in itself, to viewing it as a tool for unlocking a more meaningful and self-directed life․

Giving Back: The Psychology of Philanthropy

The act of giving, often linked to financial capacity, reveals a fascinating psychological dimension․ It transcends mere altruism, tapping into deeper human needs for purpose and connection․ Studies in behavioral finance suggest that charitable contributions often yield greater happiness than comparable personal spending․ This isn’t solely about the monetary value, but the feeling of making a positive impact․

Philanthropy provides a sense of control and meaning, particularly as wealth increases․ It allows individuals to define their legacy and contribute to causes they believe in, fostering a sense of fulfillment beyond material possessions․ The psychology of giving highlights that true wealth isn’t just about what you accumulate, but what you share․

Finding Fulfillment Outside of Financial Gain

The pursuit of wealth often overshadows the importance of non-financial sources of fulfillment․ Morgan Housel’s work emphasizes that happiness isn’t directly correlated with net worth, but with having a sense of control over one’s life and strong social connections․ Many find lasting satisfaction through experiences, relationships, and personal growth—areas where money’s influence is limited․

Prioritizing these elements fosters resilience and contentment, shielding against the hedonic treadmill where increased wealth simply raises expectations․ True fulfillment stems from aligning actions with personal values, pursuing passions, and contributing to something larger than oneself, demonstrating that a rich life isn’t always a financially rich life․

Criticisms and Limitations of the Psychological Approach

While insightful, quantifying psychological factors proves difficult; external economic conditions significantly influence financial decisions, and rationality still plays a crucial role in outcomes․

The Difficulty of Quantifying Psychological Factors

A core limitation lies in the inherent challenge of measuring subjective human emotions and biases․ While behavioral finance identifies patterns like loss aversion and confirmation bias, assigning precise numerical values to these psychological influences remains elusive․ Unlike traditional financial models relying on quantifiable data – interest rates, earnings reports – psychological factors are often inferred, not directly observed․

This makes rigorous testing and predictive modeling difficult․ Researchers often rely on surveys and experiments, which can be susceptible to self-reporting biases and artificial environments․ Furthermore, individual responses to financial stimuli vary greatly, making generalizations problematic․ Establishing a causal link between a specific psychological trait and a financial outcome requires careful consideration, as correlation doesn’t equal causation․ Therefore, while the psychological approach offers valuable insights, its lack of precise quantification presents a significant hurdle․

The Influence of External Economic Conditions

Psychological responses to money aren’t formed in a vacuum; broader economic climates profoundly shape financial behaviors․ During periods of prosperity, optimism often fuels risk-taking and speculative investments, potentially leading to bubbles․ Conversely, economic downturns trigger fear, prompting investors to become overly cautious and sell assets, exacerbating market declines․

These collective emotional shifts can override individual rational decision-making․ External factors like inflation, interest rate changes, and geopolitical events create uncertainty, amplifying existing psychological biases․ The ‘herd mentality’ becomes more pronounced during volatile times, as individuals seek safety in numbers․ Therefore, understanding the interplay between individual psychology and macro-economic forces is crucial for a comprehensive analysis of financial decision-making․

Individual Differences in Financial Psychology

Financial psychology isn’t uniform; deeply ingrained personal histories and values significantly influence how individuals approach money․ Childhood experiences, particularly those related to financial security or scarcity, shape long-term beliefs and behaviors; Some prioritize wealth accumulation as a means of achieving security, while others value experiences or generosity above material possessions․

Personality traits, such as risk tolerance and impulsivity, also play a crucial role․ Cognitive biases, while common, manifest differently in each person․ Recognizing these individual variations is vital, as a ‘one-size-fits-all’ financial strategy is unlikely to be effective․ Tailoring financial plans to align with personal values and psychological profiles enhances long-term success and contentment․

The Role of Rationality in Financial Decision-Making

While traditional finance assumes rational actors, behavioral finance acknowledges the significant influence of emotions and cognitive biases․ Humans aren’t consistently logical when it comes to money; fear, greed, and overconfidence frequently override objective analysis․ This isn’t necessarily a flaw, but a fundamental aspect of human psychology․

Acknowledging these irrational tendencies is crucial for improving financial outcomes․ Strategies like pre-commitment devices and diversified investment portfolios can mitigate the impact of impulsive decisions․ Understanding the limits of rationality doesn’t imply abandoning logic, but rather supplementing it with self-awareness and a realistic assessment of personal biases․